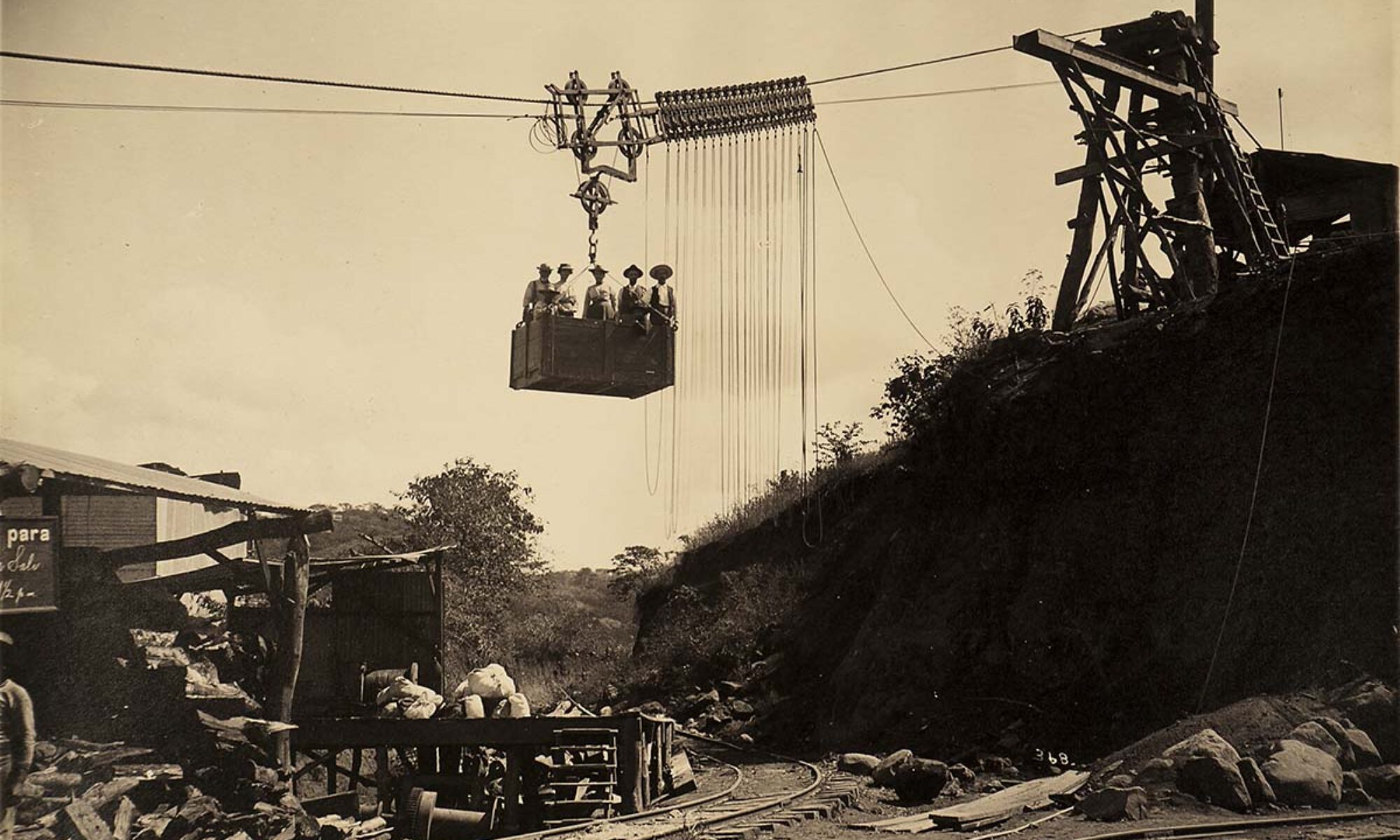

Circa 1930

To gain experience with digital software and equipment, in 1999 I digitized the albums my father created around the 1950s, with photographs his family sent him while studying overseas. I spend months removing the mold’s damage and cracks and repairing the faces, hands, and apparels of various of my ancestors. I also discovered how to use curves to adjust tone, contrast and its correlation with my venerated process in the dark room. Even more, I started to paint over black and white digital files. Painting photographs, known as “illuminating” black and white photographs, was very popular during the first fifty or so years of photography. This first course of digital photography culminated with a family book. It was a limited edition of eleven books, all hand-bounded, one for each of the Chaverri Benavides uncles or aunts.

Shortly after finishing the family book, I connected with the historian and photography collector, Manrique Álvarez Rojas, and digitized glass plates from his personal collection. This was the beginning of my bewitching with one of the first Costa Rican photographers, Manuel Gómez Miralles (1876-1965). From Manrique’s glass plates, 38 images were prepared for display. The first exhibition took place at the Casa de la Cultura in Heredia, Costa Rica in September 2005. The show was also presented in other venues in San José, including the French Alliance and the Costa Rica Country Club.

From that moment on, the search for old photographic archives and conducting research occupies a significant part of my time. I currently focus on Costa Rica old documents, and the photographic processes that became very popular all over the world, which also impacted the development of photography in Costa Rica. Among the most popular are reproductions, cartes de visite, postcards, stereograms, magic lanterns, and the small cards that came inside cigarette’s packs. One of the archives that impacted me is the collection of photographs that the United Fruit Co. donated to the Baker Library, Harvard University. Together with their vast agricultural records, images depict the building of the cities of Golfito and Quepos. Sadly, nowadays, there are just a few documents from the past of these two cities in Costa Rica. Besides, I have the honor of working with archives of foreign and Costa Rican photographers. Some of them are Harrison Nathaniel Rudd (1840-1917), the Paynter Brothers, Amando Céspedes Marín (1881-1976), Mario Roa Velázquez (1917-2004), Mario Ramírez Villalobos (1919-2001) and Alfonso Barahona Solano (1929-2013), and collections belonging to families in Costa Rica.

I am concerned over the deterioration caused by time in all the archives studied. The physical, biological and chemical decline, in many cases, could be slowed down using the proper storage conditions for all photography material.

The photographic archives of the past are a testimony of a moment that existed, and that will never happen again. The preservation and conservation, as well as its disclosure, use, and study, are critical since they are part of our cultural legacy. I do not believe that old photography is better or more valuable than today’s, nor do I feel nostalgia for returning to the past. I think those materials invite a reflection about those moments presented by photographers.

In short, my approach to old documents changed significantly from ten years ago when I concentrated on digitizing and restoring images to make them look better. Today, my goal is that the archives of photographic materials be preserved and conserved—in the best possible manner— for posterity, and digital techniques help us to make this job more manageable and with environmentally-friendly processes.

—Alejandra Chaverri

Diciembre 2018

Referencias

Bolaños, G. Carta abierta a don Manuel Gómez Miralles

Sánchez, E. El hombre con la radio por corazón

Vargas, S. Manuel Gómez Miralles—Fotografía y Memoria

Wallace, R. A Clear View