These small postcards found in family albums and antique shops represent the start of photography at massive scale. The “portrait cards” or cartes de visite, CDV, (name by which they were known throughout the world), were small albumen print impressions, of sizes around 3.5 x 2 in (8.9 x 5.1 cm). Printed on very thin paper, the CDV were mounted on cardboard of approximately 4 by 2.5 in (10.2 x 6.4 cm).

The process and camera to create CDV were developed by the French photographer André Adolphe Disdéri (1819-1889) in 1854. Disdéri patented the method of producing photographic clichés from collodion, albumin, and glass. To take the photographs, four, six, eight, and in some cases up to twelve, objectives were incorporated into the camera, maximizing performance and reducing the cost of producing. (5)

This photography genre quickly became popular throughout the world. In 1857, Queen Victoria of England contributed to its popularity with CDV of the entire royal family, and in 1859, C. D. Frederick brought them to New York.

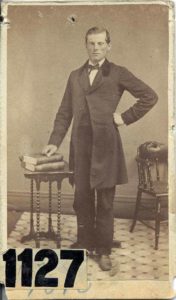

Because of its low cost compared to painting and daguerreotype, CDV can be almost thought as the “selfies” of the of the second half of the 19th century. For example, during the Civil War in the United States, soldiers and their families used CDV to create a souvenir before leaving for war. Soldiers kept CDV between the pages of a Bible or in a uniform pocket. Such was the popularity of photography at this time that between 1864 and 1866, the government of the United States imposed a luxury tax on photographs. The photographers had to put a postage stamp to each photo sold, according to the price of the image. The post stamp of 2 cents paid for prints that cost less than 25 cents is shown in the attached picture.

Gradually, studio portrait techniques used mainly for the privileged class were adapted to the bourgeoisie and the middle class. Painted backdrops emulating iconic European landscapes, elegant chairs and kneelers, balustrades, books and elements that were symbols of the people in power, intellectuals, or artists, became part of the representations of anyone who could afford a photograph. Undoubtedly, fashion and hair style of both men and women, are elements that today help to identify the decade in which the photograph was taken. In some cases, the studio had dressing rooms and lended clothes and jewelry to the customers.

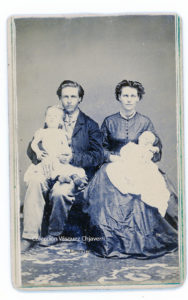

The small format of these photographs limited the space to accommodate groups. Most of the CDV were portraits of subjects alone or couples, posing in a studio. Even so, there are cartes de visite with groups of people. Children and the elderly were the most difficult sitters since they moved a lot.

Post-mortem portrait, especially of young children, was practiced during the Victorian era. The photograph on the right shows a couple with two dead children. This visiting card was purchased in the United States, and the date of the portrait is unknown. The thin cardboard that serves as a support, and the beautiful golden lines, as well as the outfits of the young couple holding the children in their arms, indicate that the CDV was taken around 1860s to1870s. The cardboard does not show a mark of the photographer, indicator of its low cost, perhaps produced by a traveling photographer.

The peak of cartes de visite was in 1860, with moderate use during the first decades of the 20th century. Cards were collected and stored in personalized albums, with leather covers and the name of the owner. By 1920, with the appearance of other photography formats such as Cabinet, Victoria, and Promenade (more substantial) or much smaller, Mignon, the use of cartes de visite discontinued in Europe and in the United States.

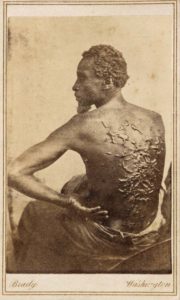

The traveling photographers commercialized the “exotic world” with photographs of people from different parts of the world, their customs, buildings, and landscapes.

Cartes de visite were also used for racial exploitation, perpetuating stereotypes. CDV also helped to divulgate injustices, social struggles, or to promote leaders.

In Latin America, cartes de visite were also very popular. There are large archives of cartes de visite in Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Brazil, Mexico, and Cuba. Costa Rica also embraced this photography format. In Costa Rica, photographers also emulated the style of portrait used for painting for the cartes de visite. The ladies were dressed neatly, wearing sophisticated hairstyles and dresses, complementing the attire with Spanish shawls or “mantillas”, embroidered or lace collars and jewelry, which highlighted their aristocratic status. It was common the display of religious elements, such as rosaries, medals, and crucifixes on the chest, or books that hinted at the intellectuality or religiosity of the subject portrayed. Since cartes de visite competed with the genre of painting, many were colored, technique known as “illuminating” a photograph.

In her book “La Mirada del Tiempo,” (8) the photographer Sussy Vargas mentions William Buchanan, as the person who introduced the cartes de visit to Costa Rica. Buchanan was an itinerant photographer of English origin, who arrived at Costa Rica in 1852. He traveled frequently, to the United States and went to several Central American countries and Mexico.

At present, we still find cartes to visit in Costa Rica, dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Some were taken by the US photographer Harrison Nathaniel Rudd (1840-1917), and by the Paynter Brothers. Others followed Rudd and the Paynter Brothers, including the new photographers Felix Robert, Hermanos Hernández and Manuel Gómez Miralles. During the 1930s, Gómez Miralles was still making cartes de visite, to commemorate the day of First Communion of many children of the Central Valley. The carte de visite gave way to the “closet postcards;” the photographers imported thicker papers for their photographs, adopted the use of gelatin silver print instead of albumen print. By 1950, photographers stopped making of cartes de visite in Costa Rica.

At present, we still find cartes to visit in Costa Rica, dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Some were taken by the US photographer Harrison Nathaniel Rudd (1840-1917), and by the Paynter Brothers. Others followed Rudd and the Paynter Brothers, including the new photographers Felix Robert, Hermanos Hernández and Manuel Gómez Miralles. During the 1930s, Gómez Miralles was still making cartes de visite, to commemorate the day of First Communion of many children of the Central Valley. The carte de visite gave way to the “closet postcards;” the photographers imported thicker papers for their photographs, adopted the use of gelatin silver print instead of albumen print. By 1950, photographers stopped making of cartes de visite in Costa Rica.

The universal success of the cartes de visite, along with other processes of the late nineteenth century such as stereograms and magic lanterns, contributed to improve photographic techniques, materials, and equipment. These small photographs are an invaluable source of visual information regarding fashion and trends, the photographers and the evolution of the printing industry. Like any photograph, cartes de visite are subject to deterioration. Proper care and storage are necessary to preserve these small fragments of the visual history of a community.

If you enjoyed this article, share it with others. Comments and questions are welcome.

Cheers,

—Alejandra Chaverri

Diciembre, 2018

*Harrison Nathaniel Rudd (1840-1917) fue un fotógrafo de Estados Unidos que se mudó a Costa Rica in 1873. Durante 40 años practicó la fotografía en Costa Rica, documentando la vida cotidiana y los cambios que ocurrieron en el país al final del siglo XIX. Él murió en San Diego, California en 1917. Esta fotografía pertenece a los archivos militares del estado de New York. Rudd se enlistó como soldado durante la Guerra Civil de Estados Unidos, en 1862 y fue dado de alta en 1865.

Referencias

1. Darrah, W. C. (1981) Cartes de Visite in Nineteenth Century Photography. Gettisburg, PA, W. C. Darrah Publishing.

3.Lansdell, Avril. (1992). Fashion à la Carte, 1860-1890. Buckinghamshire. UK. Press Building. 2nd ed.

4.Luminous-Lint. On line exhibition of Cartes the Visite

5.Rosenblum, N. (1997) 3rd ed. A World History of Photography. Aveville Publishing Group. NY. US.

8.Vargas S., Alvarado, I., Hernández, E. (2004) 1st. ed. La Mirada del Tiempo. Historia de la Fotografía en Costa Rica 1948-2003. Fundación Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica.